Destiny Deacon

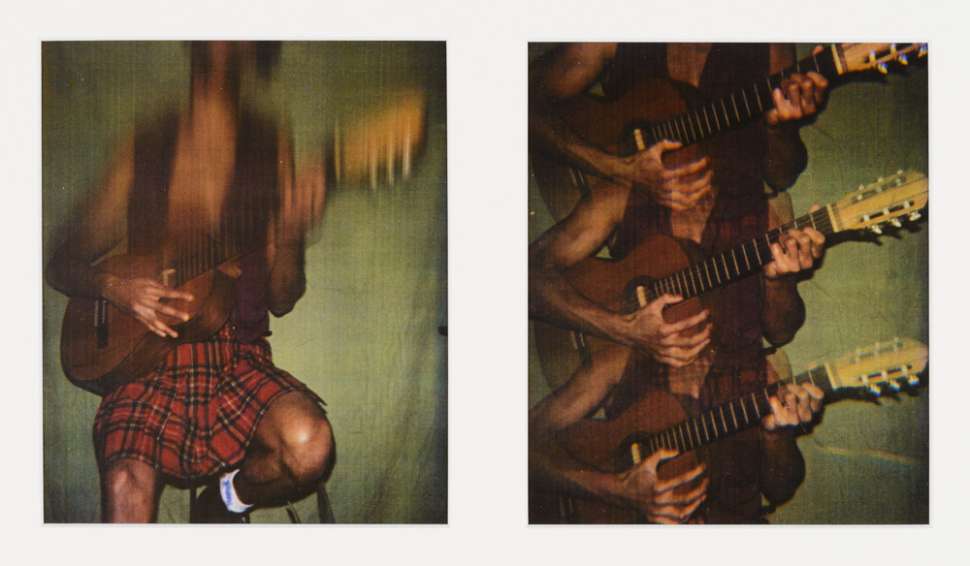

If I couldn't laugh then somedays I wouldn't stop crying.

When you are with your mob the opportunity to laugh is always present. The madness of our laughter sometimes is the only thing that keeps us going.

My mum once wrote a poem about the cold laugh of the white dominant, the stiff cold laugh of those who don't care about injustice, who use more of the world's resources, who believe they are more deserving, who enact and engage in arrogant perception.

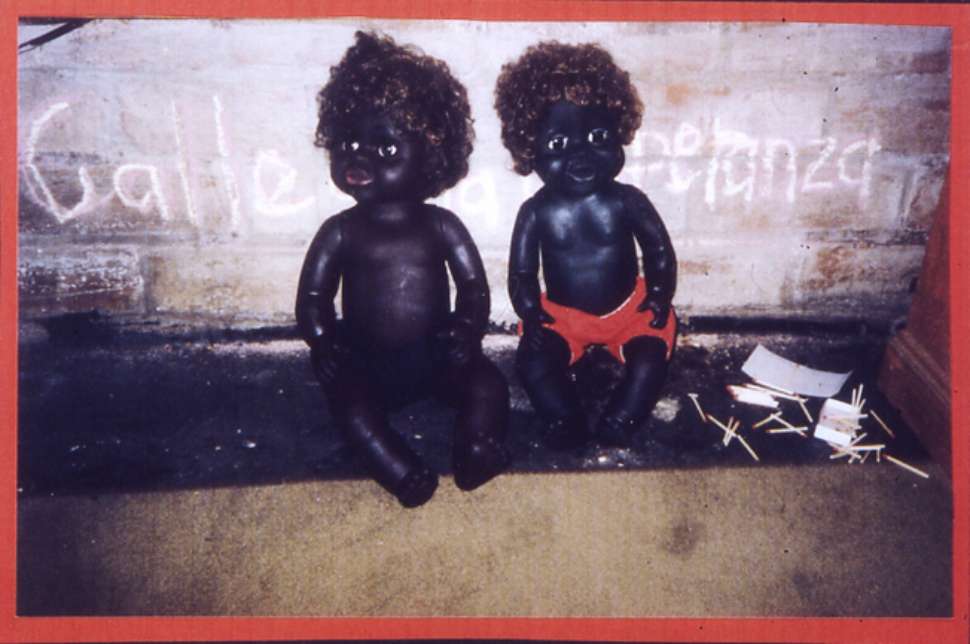

Destiny Deacon's work reminds us of our resistance through laughter, she reminds us that we can laugh at the oppression and we can laugh at ourselves and that this is what makes us human and not black dolls to be played with.

Deacon's 'blak' dolls have been with me since I started university and I always think of her deeply theoretical work; her dolls, her lost blak dolls that she found in second hand shops, bringing them home, the mob never leave us by ourselves .... and in all the best ways you can find acceptance of your damage in the community you can find acceptance of your dysfunction and you can find love.

More recently in Darwin I saw an installation of Deacon's black dolls set up in 24HR Art gallery in Parap. It made me smile to see the dolls sitting there all straggly, over worked and dodgy. I love the dodgy display ... I love the irreverence. The deep laughing and observational practice, the role reversal, the gamin play. Deacon speaks to me of whiteness. Of shiny whitey mission mob, of our innocence and how we are treated as child like savages.

I am also reminded of the houses of my Aunties from the 1970s and the proud use of the Nunga colours and the collections of Aboriginal figurines in our black homes. These white ceramic representations of us as child like picininis and needing to be looked after and collected onto missions. But in the homes of my political family these representations served to remind us that because we are sovereign and visible as dolls to the white people, we could only share our innocence with each other. And it reminded us that these paternal representations required us to remain staunch and angry with the goonyas.1 They did not deserve our humour. We are proud of our histories and when they are painful we are proud of our scars of survival. Sometimes we are too proud of our dysfunction, and then we need to be reminded that our children also need to have their innocence and love and Nunganess protected. So then we need outlets for our anger and what better way to let go of your anger than through laughter.

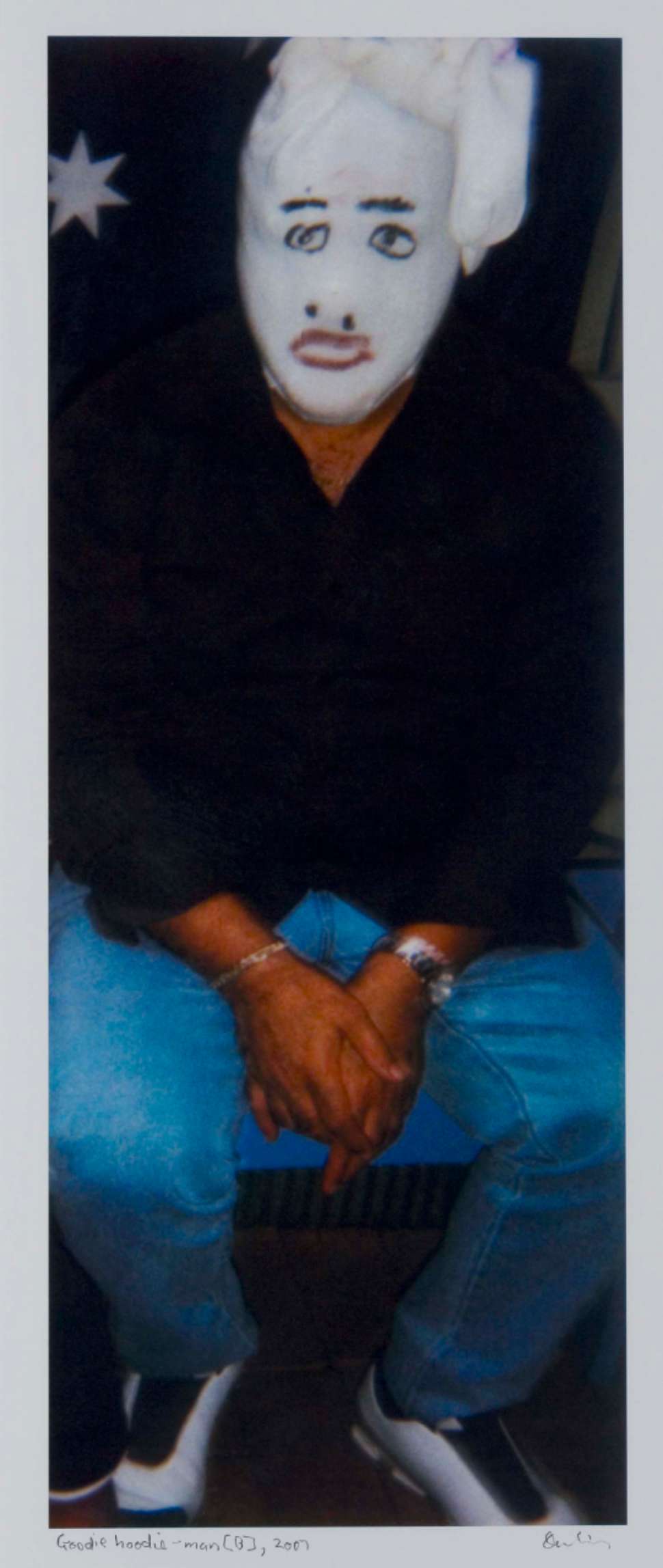

The face of the white balaclava in Deacon's work Fence Sitters disturbs me and I can hardly look at this image on the pillow, let alone let this face smooth my dying pillow before I fall into the gap.

Through the space this work creates I remember the flag waving of Invasion Day and the young faces of invading white primitives drunkenly swaying, wrapped in the colonising flag. It is a frightening space for Aboriginal people. It is collective amnesia on a mass scale that is violent and possessive. It causes us Nungas to be invisible and visible all at once and without recognition of our sovereignty.

Deacon reminds us that we resist nationalism when that nationalism excludes us.

This text is an edited essay by Mirning artist and academic Ali Gumillya Baker, first published in the exhibition catalogue

Long Way Home: A Celebration of 21 Years of Yunggorendi First Nations Centre (2011), p. 6.

1 Kaurna word for white people in Survival in our Own Land: 'Aboriginal' Experiences in 'South Australia' Since 1836 I told by Nungas and others 1988, Mattingley, Christabel & Hampton, Ken (eds.) Wakefield Press, Adelaide, p. 4.

Ali Gumillya Baker

Associate Professor, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University

September 2024

© Flinders University