As scientists around the world scramble to find a solution to the growing crisis around multi-drug resistant bacteria, a Flinders University professor has found one answer in a most unlikely place – the Glenelg sewage works – where he is isolating bacteriophages, the viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria, killing them in the process.

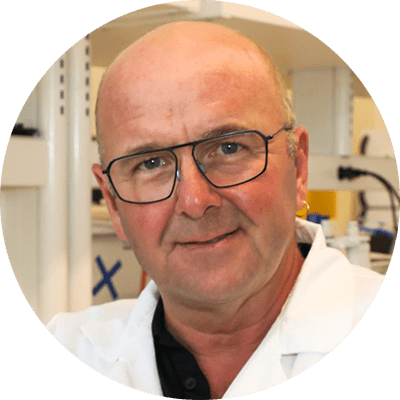

Professor Robert Edwards, the Director of Bioinformatics and Human Microbiology for the Flinders Accelerator for Microbiome Exploration (FAME), became interested in bacteriophages, more simply called phages, in the very early 2000s when DNA sequencing was helping unlock the secrets of these minute assassins.

“We were very interested in trying to understand how many phages there are in the environment or in our bodies or other places,” Professor Edwards says. “You can't culture them directly, you need to get the bacteria and then isolate the phage, and DNA sequencing is one of the easiest ways to do that.”

We have known about phages for more than 100 years and have long understood how they selectively target and kill bacteria. Looking like they might be tiny alien spacecraft, they attach themselves to the cell walls of bacteria, penetrate the surface and inject genetic material witch disrupts the bacteria’s normal operations, recruiting them to replicate the phage instead.

While their potential as a weapon against bacterial infection was recognised early, the advent of antibiotics put research on hold. Now, with the arrival of bacteria that are antibiotic resistant, the phage is back in fashion.

That has been helped by high profile cases where treatment with phages has saved patients when all else has failed.

“There was a famous case in California in 2016 where a professor at UC San Diego travelled to Egypt and got a bacterial infection which didn’t respond to any antibiotics. His wife, who was also a professor in epidemiology, got hold of some phages and treated him and within a few days he was out of a coma and able to speak with his family,” says Professor Edwards.

There are a couple of challenges, however. First, specific phages only attack specific bacteria and so they must be matched. Then the challenge is to grow enough of them to treat the infection.

Enter Glenelg sewage works.

“In my lab at Flinders we have been isolating phages from sewage from Glenelg and also working with SA Pathology, where they have a lot of problematic bacteria that are multi-drug resistant. So they give us the bacteria, we isolate phages against those bacteria, we characterise them through genomics and provide the phages back to hospitals to treat patients,” Professor Edwards says.

Currently the Flinders team is working with a patient at Westmead Hospital in New South Wales, and Professor Edwards anticipates providing phages to the Royal Adelaide Hospital within a year.

Nevertheless, the process of matching and producing the right phages is complex and slow. Professor Edwards foresees a day when hospitals have “libraries” of phages at their disposal.

“We are building up stocks of the phages that we've characterised, so we don't have to go back to the start. But one of the things that I'm very enthusiastic about is using some new synthetic biology ideas so that instead of going to the sewage, we can create those in our laboratory, so we can create those phages.”

Professor Edwards is ideally suited to the task. While his background is in microbiology, through his interest in genomics and bioinformatics he learned a lot of computer science, even becoming a professor in it for a while, hosting a YouTube channel where he presented classes on computer science.

The FAME lab reflects his own duality.

“It’s unusual because it's a real mix of people who just sit in front of computers all day doing bioinformatics, and people who go and work in the laboratory and do experiments. I work hard to keep those two things in balance because it's very easy to have a bunch of computer scientists sitting around thinking they've got an answer, or a bunch of biologists sitting around thinking, ‘I wish I knew how to analyse this data’. And so my lab is pretty much half-and-half, experimental biologists wearing lab coats, growing bacteria, and then people sitting in front of computers writing code.”

The focus on phages, while dramatic, is only one of FAME’s interests, which range from wildlife monitoring to helping cystic fibrosis patients adapt to new medications.

“We’re working on human-associated microbiomes and viruses in particular, in my group, but there are a lot of people in Flinders and in South Australia who are really interested in this problem – not just people associated with human health but the health of other things,” says Professor Edwards.

Some of those projects are looking, for example, to understand how the microbiome affects sharks and, tangentially, trying to identify what sharks are attacking and why, through DNA sequencing.

“One of the things that we're trying to do with FAME is to share our experiences to try and lift everybody up and enable everybody else to do the kinds of science that we do to understand the microbiome. And that's really one of our fundamental goals – to get people working in the right direction, help them with that preliminary data and analysis, show them how to get started, show them how they can take those steps to try and understand what's going on.”

Professor Edwards foresees a day when hospitals have “libraries” of phages at their disposal.

![]()

Sturt Rd, Bedford Park

South Australia 5042

South Australia | Northern Territory

Global | Online

CRICOS Provider: 00114A TEQSA Provider ID: PRV12097 TEQSA category: Australian University